As a child, seeing a brumby was an event, shaken from the boredom of a family roadtrip through the alps, into sheer excitement.

An elusive, yet elegant creature, braving the harsh climates of Australia. The perfect analogy for high country Australians, who established a life where none thought they could.

However, in the last two decades, the conversation of brumbies has changed from romance to controversy.

The reason? something Australia knows all to well, invasion and destruction of native land.

Brumbies have been a part of Australian Alps for nearly 200 years and have defined the culture of the high country.

Romanticized and almost deified by the locals, the brumbies significance in Australian icon is not to be underestimated, their imagery present all throughout history.

Populations have been increasing dramatically and the cumulative damage on the native wildlife is reaching a tipping point.

However, the aerial culling required to control the numbers is controversial for many.

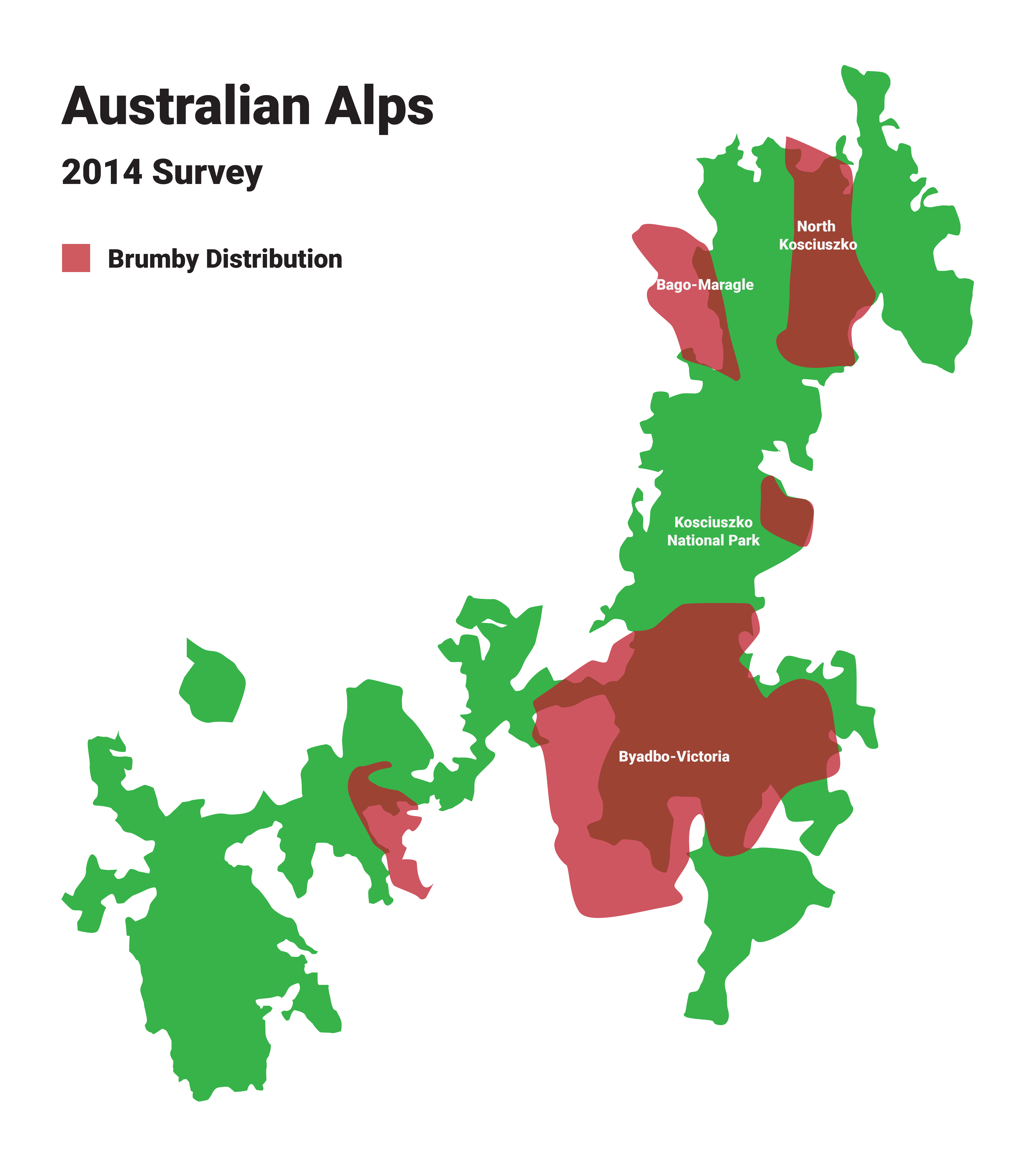

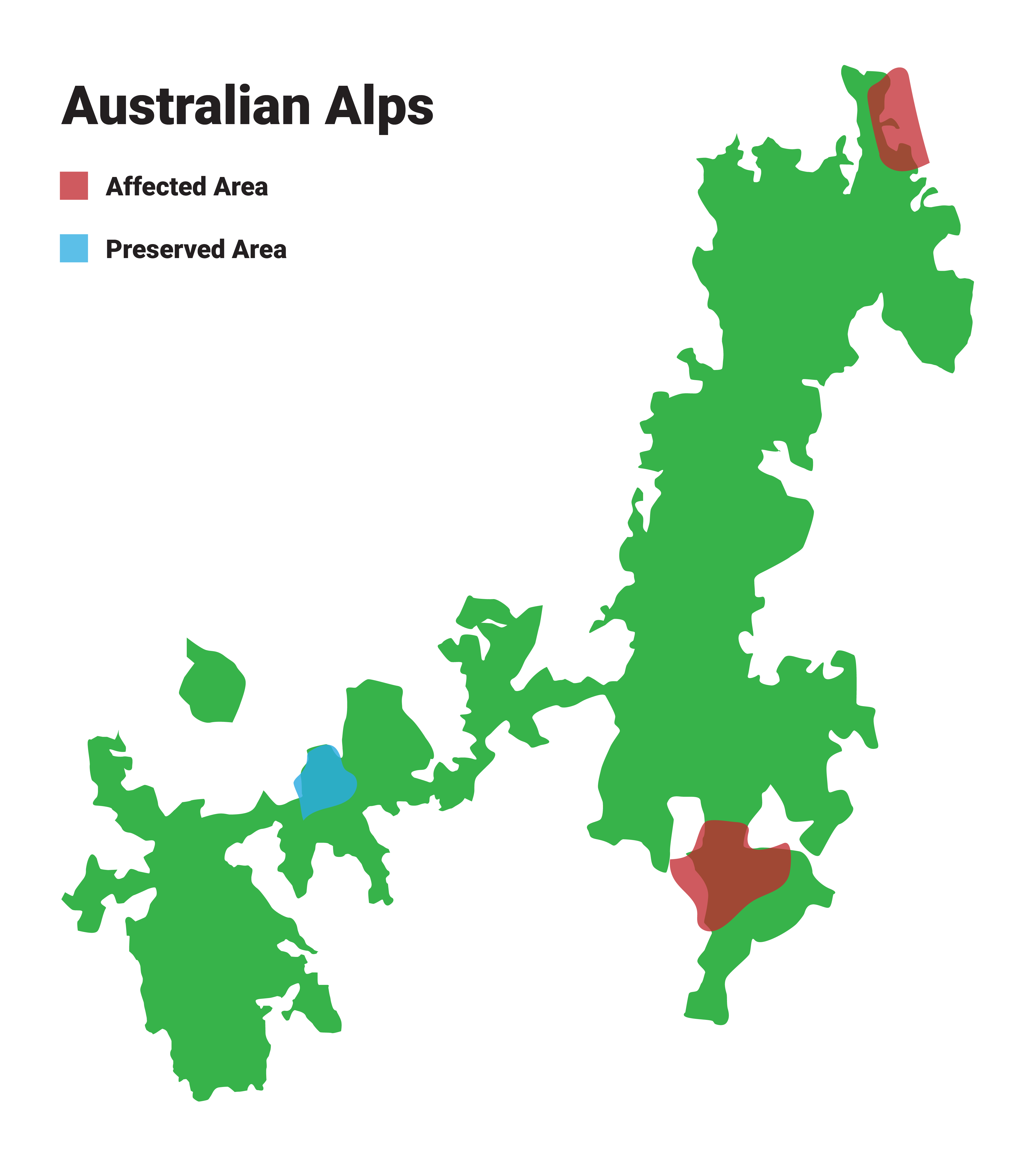

The main home of the brumby is the Australian Alps, a mountainous region spanning across the Australian Captial Territory, New South Wales, and Victoria.

Their populations scattered across the regions of this stunning landscape.

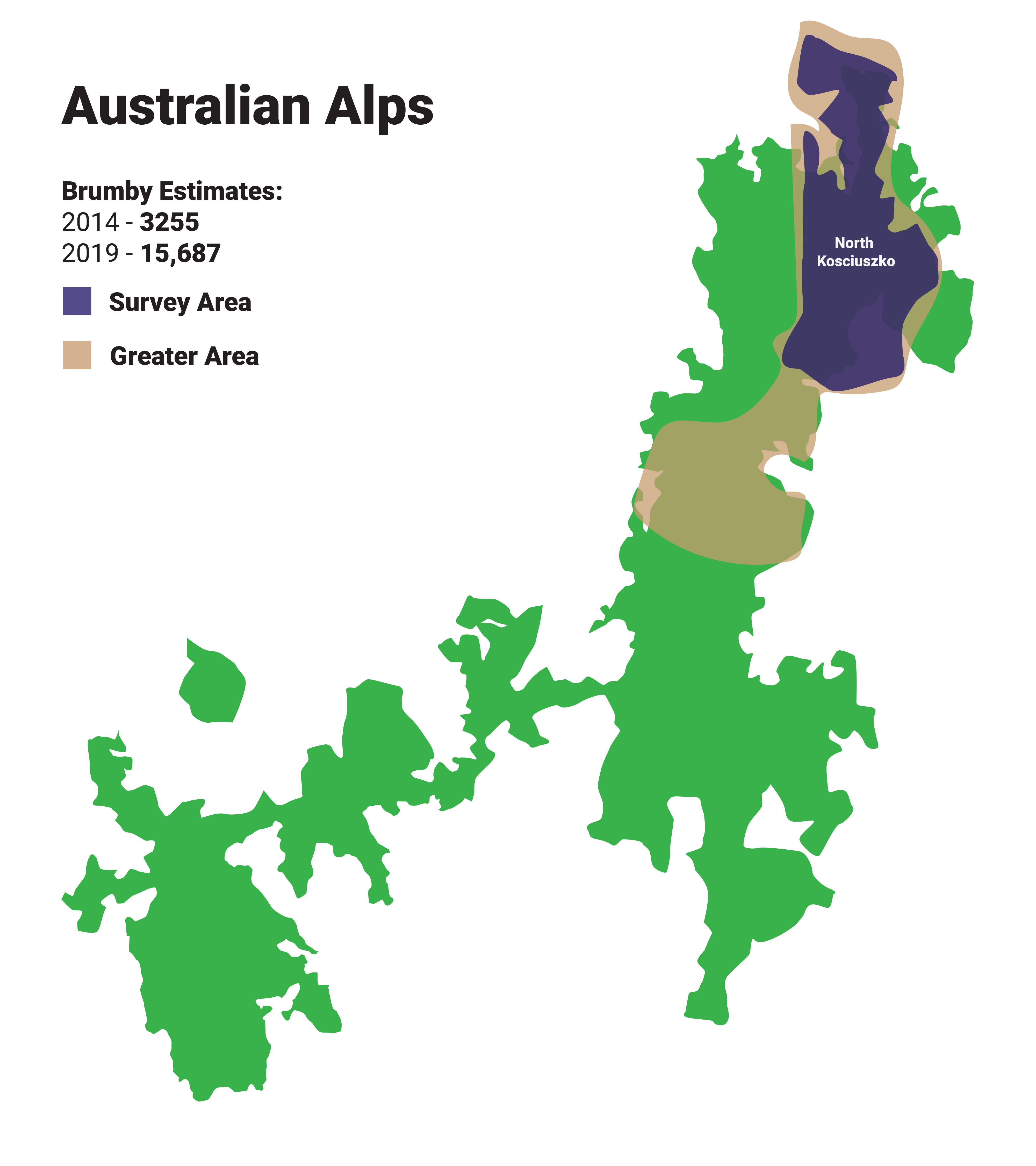

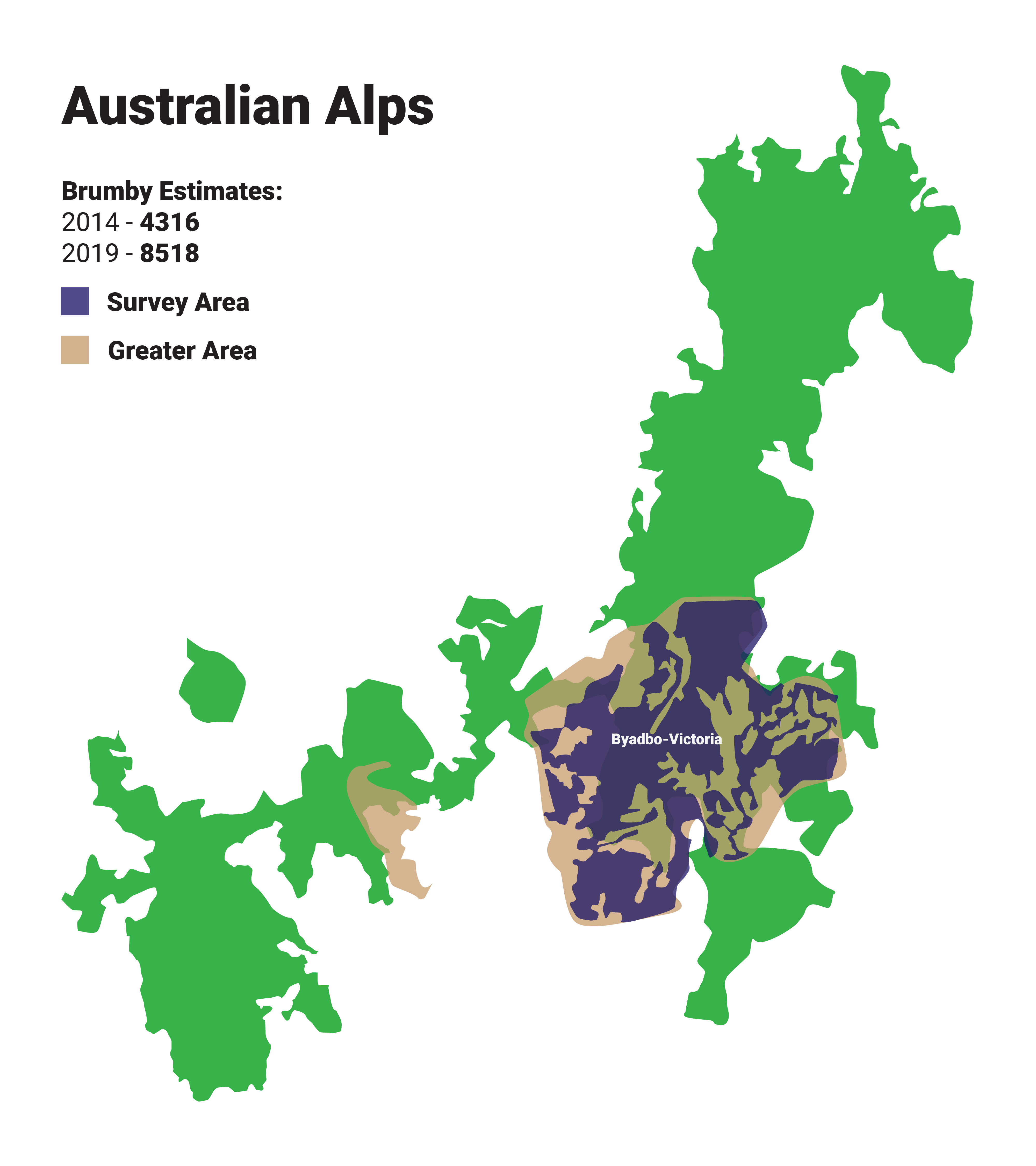

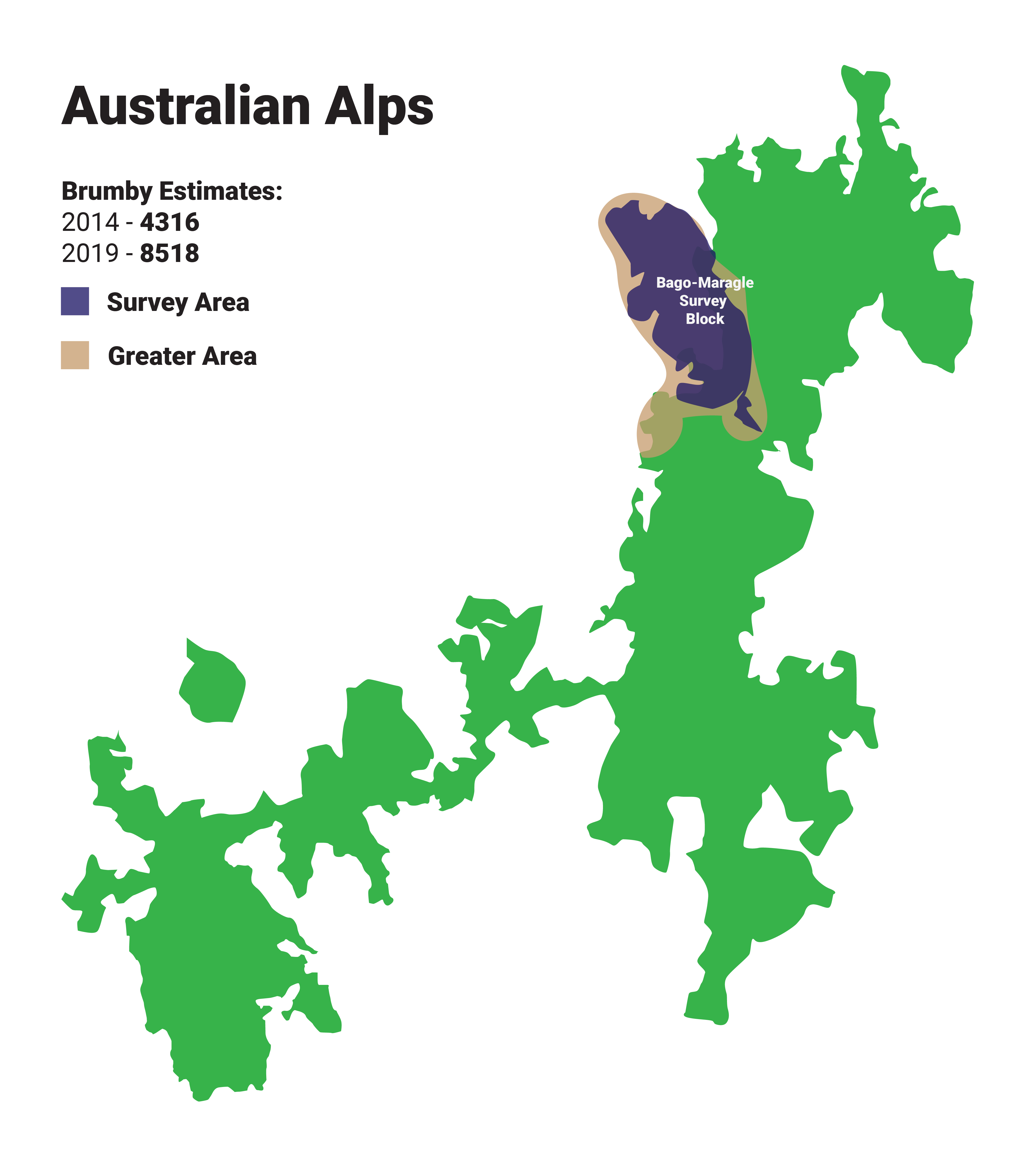

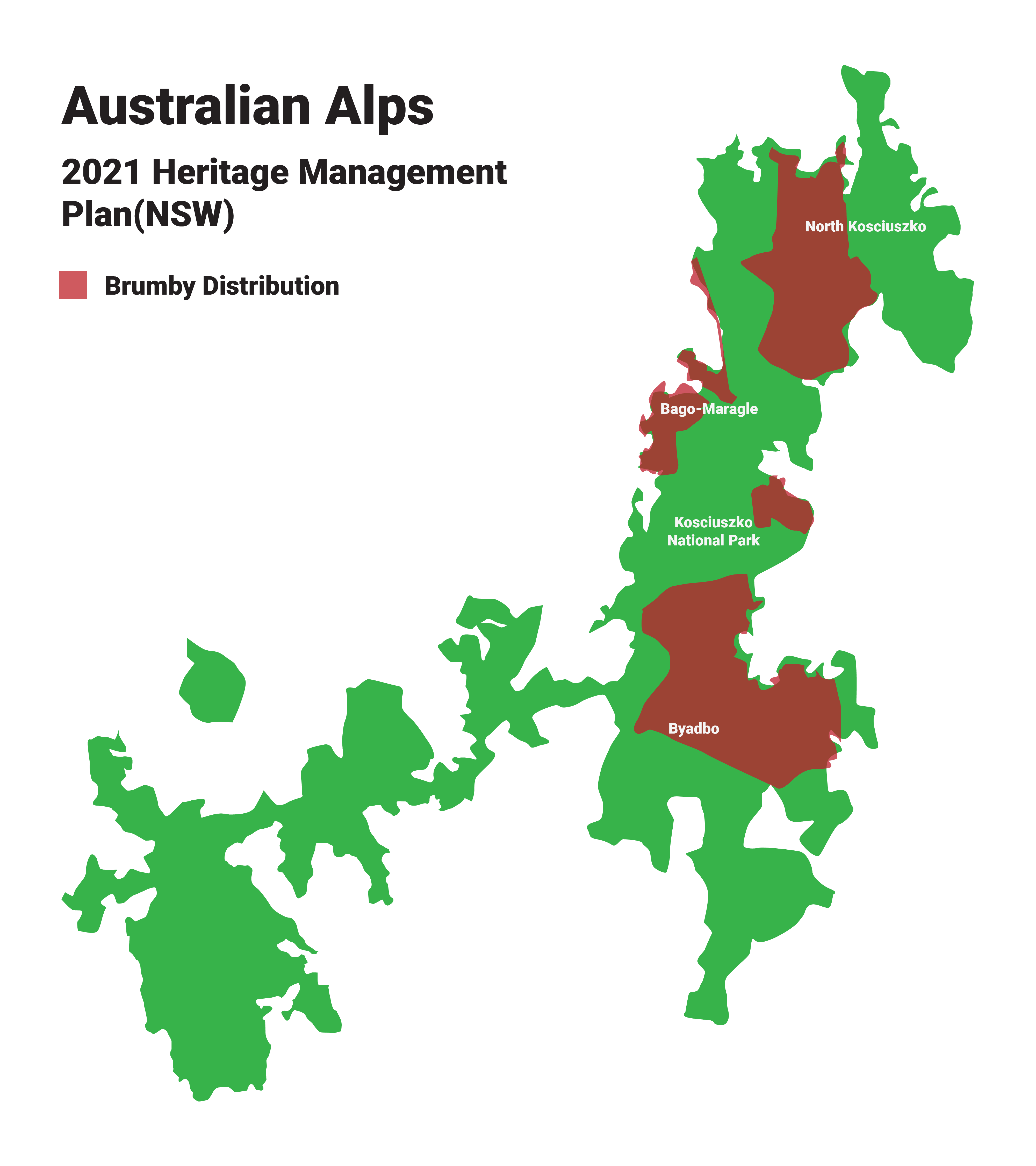

A survey conducted by the Australian Alps National Parks collective in 2014 identified 3 key regions of brumby habitat, Bago-Maragle, Kosciuszko, and Byadbo-Victoria.

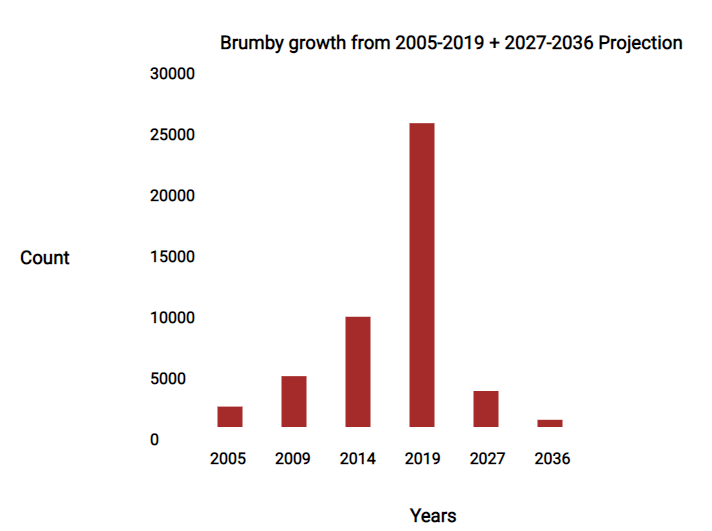

Through aerial surveying, an estimate for the brumby distribution was calculated, along with a total estimated population of 9187.

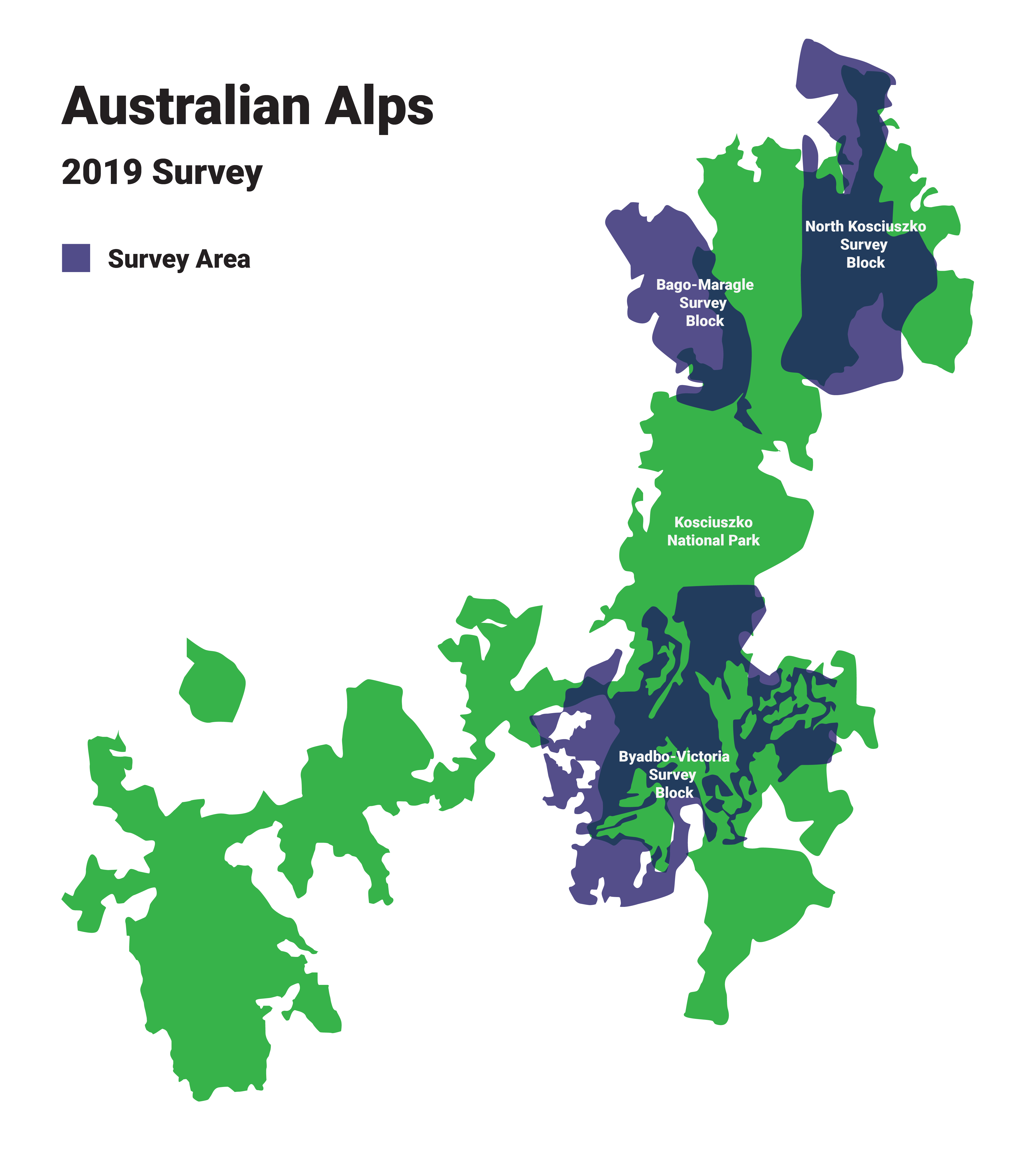

This survey was then repeated in 2019, analysing the same regions.

It found that in the 5 years since the last survey, the projected population of brumbies in the Australian Alps had increased by over 15,000 to an estimated 25,318.

Meaning that the population was growing at an alarming 23% per annum

Examining closer, in Kosciuszko National Park, estimated brumby populations exponentially grew from 3255 to 15,687.

This was by far the most concerning statistic and the safety of the Kosciuszko eco-system was quickly becoming a concern.

In the Byadbo-Victoria area, populations have nearly doubled increasing from 4316 to 8518.

While in the Bago-Maragle area, populations decreased by an estimated 500 brumbies, from

1616 to 1113.

Despite this outlier, the overall trend is positive, which spells disaster for the native ecosystem.

This graph shows the increasing rates of brumby numbers, putting into perspective the rate at which these numbers are increasing.

An animated version can be found here

To understand the reason for growth, we have to look back on their history in Australia.

The wild brumbies we see today most likely originate from Sergeant James Brumby's horses released after when transferred to Van Diemen's Land around 1806.

When these horses were released, they were the first to establish a presence in the mountain that thus dubbed the name Brumby to them.

These horses, along with escapees from owners during World War I and the Great Depression began reproduction without the domestication of humans.

When freed, the horses that survived were the ones that were calm and were able to save more calories unlike the horses with a tempered personality.

This left the sturdy and calm ones to survive and reproduce as the spared calories gave them extra time to find natural resources.

After a while, their genes have been reduced to less than 5% inbred unlike their domesticated counterparts.

Initially, being released in to the wild after years of domestication on top of facing the harsh mountain environment and wildfires slowed down their reproductive numbers.

However, after years of tempering they have come back in full force.

The brumbies cause the destruction and damage of native species that slowly degrade the ecosystem.

This also extends to animals as researchers noted the impact of reptiles and small mammals having their homes destroyed due to the trampling.

Because ecosystem recovery is naturally slow, even the smallest numbers can have long term effects.

The brumbies will trample into stream beds and damage its structure causing erosion that will leave larger dirt particles in the streams that will pollute the water once the smaller particles wash downstream.

In addition, the trampling will remove roots which will ruin the structure of the bed entirely.

Since some of these areas contain unique vegetation undisturbed by hooved animals, they've become very fragile and any brumby contact can easily destroy them.

The following pictures are a compilation of destruction evidence in Kosciuszko National Park showing the damaged water systems and patched vegetation caused by the trampling and rolling.

Some include pathways created by the brumbies that disturbed the growth areas of the moss and grass.

In these images it is easy to see how the hard hoofed brumbies flatten and tear the soft banks of the National Parks

Professor James Pittock from the ANU Fenner School of Environment and Society, has joined many surveys of the Australian Alps as a part of a large scientific cohort aiming to protect the native wildlife of the ecosystem.

"The worst areas that I've seen recently are the 'pine clad ridges' rain shadow country along the Snowy River and the catchment of the upper Murrumbidgee River. " Says Pittock

"The damage in these places is systematic and will take decades to heal once the feral horses are removed."

"By contrast, areas protected by exclusion fences on the Victorian Bogong High Plains since the 1940s stand out with more vegetation, no erosion and a greater diversity of plant species."

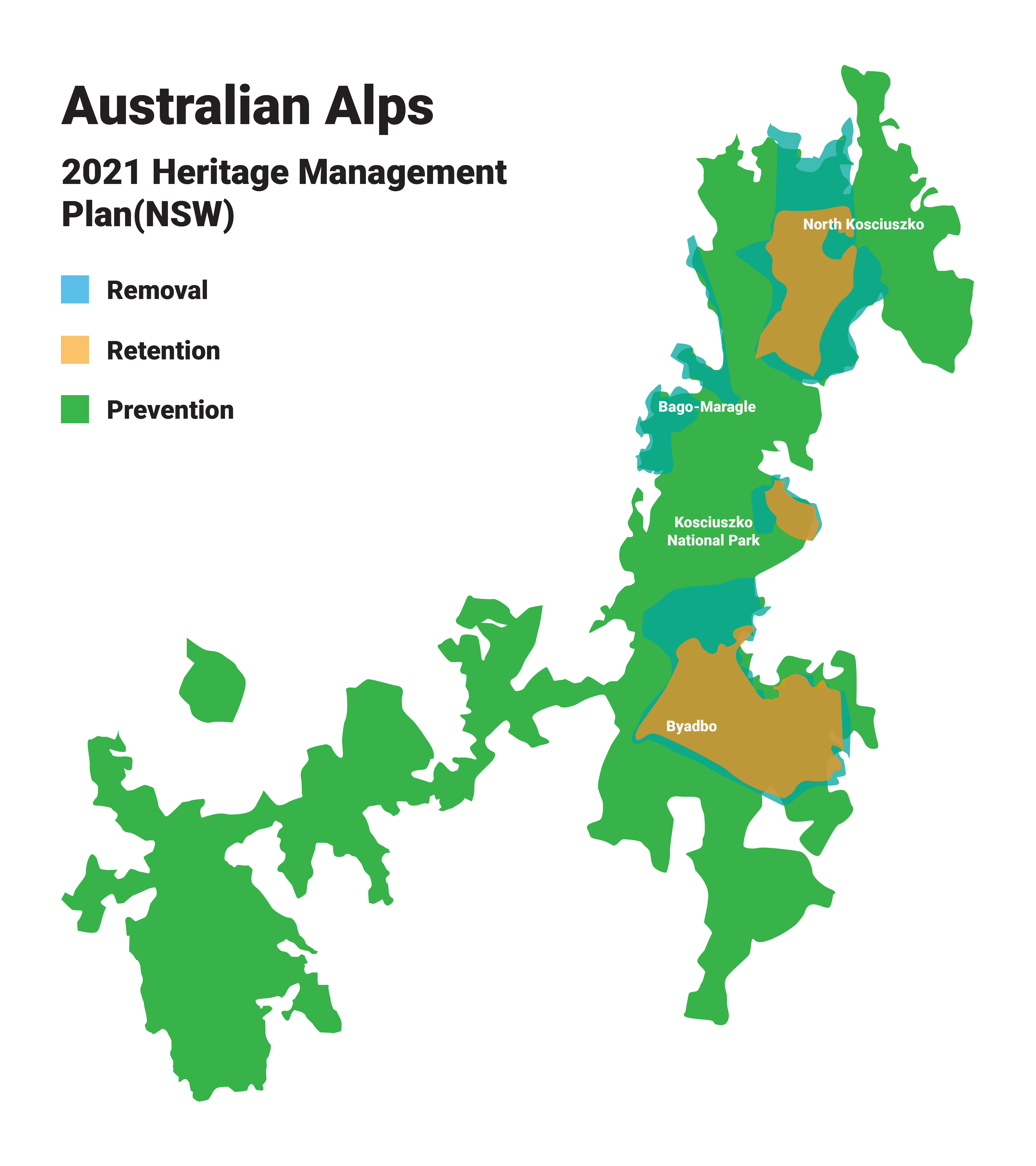

Luckily in 2021 the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service implemented a new wild horse heritage management plan for Kosciuszko national Park.

Which aims to control and reduce horse populations.

The plan has three steps retention (32% of the park), removal (21% of the park) and prevention (47% of the park). with a goal of decreasing numbers down to an estimated 3000 by 2027.

Because of the climbing numbers, aerial culling has now become a necessary option to reduce the brumby population

As seen in other countries with massive horse populations like the U.S, rehousing has been shown to be a prolonged expense and hasn't helped in controlling numbers.

That aside, when that option is unavailable, the best solution is to get rid of the adults in mass than trying to manipulate their breeding patterns.

However, many researchers argue that it will be too little too late, and the only way to avoid permanent and unrecoverable damage is immediate action and to remove the brumbies in their entirety.

Alexis Telles and Anders Coia - ANU School of Art and Design

A special Thank You to Professor Mitchell Whitelaw and Professor James Pittock for their contributions

Davis, Jess, and Alison Middleton. “In Australia's Peaceful High Country, a Bitter Conflict Is Hidden.” ABC News. ABC News, August 21, 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-21/brumbies-battle-in-nsw-high-country-kosciuszko-national-park/100372254.

Hagis, E., and J. Gillespie. “Kosciuszko National Park, Brumbies, Law and Ecological Justice.” Australian Geographer52, no. 3 (2021): 225-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2021.1928359.

Driscoll, Don A., Graeme L. Worboys, Hugh Allan, Sam C. Banks, Nicholas J. Beeton, Rebecca C. Cherubin, Tim S. Doherty, et al. “Impacts of Feral Horses in the Australian Alps and Evidence-Based Solutions.” Ecological Management & Restoration 20, no. 1 (2019): 63-72. https://doi.org/10.1111/emr.12357.

“Australian Brumby Alliance- The Origins of Australia's Wild Horses Kosciuszko's Snowy Brumby.” Australian Brumby Alliance. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://australianbrumbyalliance.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2.1-Origins-of-Australias-Wild-Horses.pdf.

Porfirio, Luciana, Ted Lefroy, Sonia Hugh, and Brendan Mackey. “Monitoring the Impact of Feral Horses on Vegetation Condition Using Remotely Sensed Fpar: A Case Study in Australia's Alpine Parks.” Parks 23, no. 2 (2017): 27-38. https://doi.org/10.2305/iucn.ch.2017.parks-23-2llp.en.

Robertson, Geoff, John Wright, Daniel Brown, Kally Yuen, and David Tongway. “An Assessment of Feral Horse Impacts on Treeless Drainage Lines in the Australian Alps.” Ecological Management & Restoration 20, no. 1 (January 30, 2019): 21-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/emr.12359.

Victorian National Parks Association. “Feral Horses in the Alpine National Park.” Victorian National Parks Association. Victorian National Parks Association, February 26, 2018. https://vnpa.org.au/feral-horses-alpine-national-park/.

Association, Victorian National Parks, and David Bill Kosky. “Horse Damage in Alpine Park.” Flickr. Yahoo!, October 28, 2022. https://www.flickr.com/photos/vnpaflickr/sets/72157688198711313/.

“Brumby Horses.” Horses. Cerf Horses. Accessed October 28, 2022. http://www.cerfhorses.org/brumby-horses/.

View, The Herald's. “Brumbies Are Destroying Kosciuszko National Park and Must Be Removed.” The Sydney Morning Herald. The Sydney Morning Herald, January 13, 2021. https://www.smh.com.au/environment/conservation/brumbies-are-destroying-kosciuszko-national-park-and-must-be-removed-20210113-p56tv5.html.

Draft Kosciuszko National Park Wild Horse Heritage Management Plan § (2021).

Lowrey, Tom. “Brumby Numbers Boom in Kosciuszko under Controversial New Legal Protections.” ABC News. ABC News, December 16, 2019. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-12-16/brumby-numbers-boom-in-kosciuszko-under-new-legal-protections/11801386.